The Big Deal About Palm Oil in Chocolate

July 21, 2024

Dark Chocolate

July 21, 2024Cocoa Shortage and Rising Prices in 2024

What Consumers Should Know

From October 2023-June 2024, cocoa farmers in Ivory Coast, the world’s largest cocoa producer, shipped 1.5MMT of beans to ports, a 30% decrease from the same period last year and an 8-year low. In March 2024, Ghana’s Cocoa Board reported that the 2023-24 harvest season will see a 50% reduction from the country’s initial forecast, a 22-year low. Drops in harvests are also projected for Nigeria and Cameroon. These 4 West African countries account for about 75% of the world’s cocoa bean production, so declines in their harvests are bound to have significant impact on global cocoa prices.

But the big question is, what is causing these poor harvests?

We look at the direct and indirect causes of cocoa bean shortages and rise in global prices.

Chronic low prices and chocolate traders’ refusal to pay living income premiums

Yes, cocoa prices are high now, but only because there’s bean shortage due to poor yields. For decades, chronic low cocoa prices have hindered farmers from maintaining aging plantations and investing in essential farming inputs such as fertilisers and disease-resilient trees.

It’s important to note that while cacao trees can live up to 100 years, cultivated trees are only economically productive for about 60 years. Yet for these years, what farmers have been receiving barely feeds them and avoid child slavery, not enough for them to invest in planting newer trees.

While everyone seems to blame climate change for the current prices, fluctuations in weather conditions have only exacerbated a situation which farmers and governments of producer countries have decried for long.

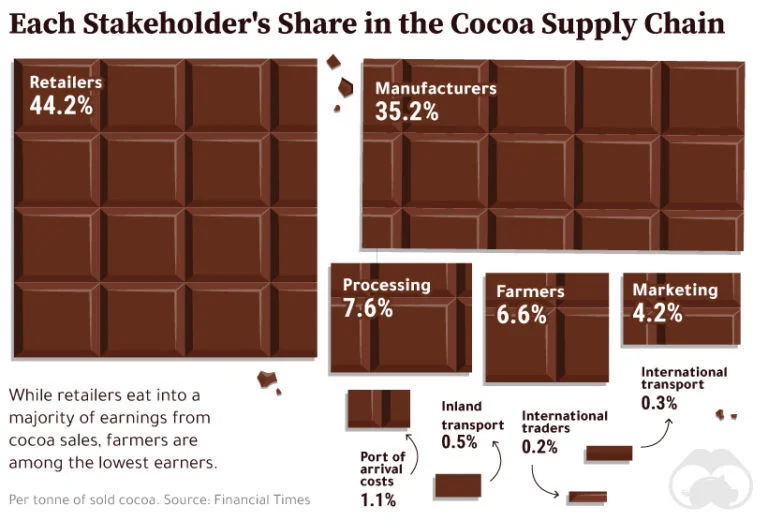

Of the over 100 billion USD chocolate industry’s worth, only about 2% trickles down to the African cocoa producers, the remaining over 90% distributed largely between manufacturers and retailers in the West. The low pay has a trickle-down effect, preventing farms from maintaining ageing plantations dating back to the end of the colonial era.

Peter Shoenmakers, head of impact at Tony’s Chocolonely, believes chocolate companies have enough room to distribute wealth down the supply chain while still making a profit. He says, “At the end, it is a matter of choice whether you want to maximise your profits at the expense of extreme poverty.”

Unfortunately, most chocolate companies choose profit maximisation. Even when driven to pay higher for cocoa, some of these companies look to shift the price increase to consumers by increasing chocolate prices or reducing pack sizes.

In 2019, the government of Ivory Coast, the world’s largest cocoa producer initiated the Living Income Differential, a $400 premium/metric tonne of cocoa that goes directly to cocoa farmers. Ghana, the second largest producer, soon adopted the initiative. But chocolate traders refused to welcome the idea of improving farmer incomes.

Poor Harvests Fuelling Bean Shortages and High Prices

Several factors contribute to poor harvests and shortages in cocoa bean supply. The direct causes include underinvestment in aging plantations (due to chronic farmer poverty), climate change-induced weather conditions, and swollen shoot viral disease.

The cocoa tree needs constant attention as it is highly sensitive to weather fluctuations. But without decent incomes from their produce, most farmers are unable to maintain their farms with quality varieties and other farming inputs, leading to poorer harvests. Add this to the burden of climate change and disease, and it is no wonder that cocoa yields are hitting new record lows in these producer countries.

Governments of Producing Countries also Pushing for Higher Prices to Improve Farmer Incomes

Besides the living income differential, another way governments mitigate poverty is through farmgate prices which are prices at farmer selling points. In April 2024, the Ivory Coast government increased the farmgate price by 50% from 1000 francs CFA (~$1.64) to 1500 CFA (~$2.46) per kilogram of cocoa beans. Ghana soon followed with a 58% increase in price per metric tonne, which translates to 34.5 Cedis (~$2.30) per kilogram. The LID will mean an additional 40 cents per kilogram.

As the world’s largest cocoa producers, Ivory Coast and Ghana can leverage their collective power to demand more income for their hard-working farmers. Unfortunately, the success of policies like the Living Income Differential largely depends on chocolatiers embracing it. Which they don’t.

Yves Ibrahima Kone, Ivory Coast’s director general of the national Coffee-Cacao Board, says no chocolate maker wants to pay the LID premium. And some of these companies do find ways to avoid paying premiums altogether. For example, Reuters reported in 2020 that the American chocolate giant, The Hershey Company, bought thirty thousand tonnes of cocoa through the ICE futures market to avoid paying the African price premium.

How the Futures Market Works

The futures exchange is an auction market where buyers can get commodities, including cocoa, at current price to be delivered on an agreed future date, even if market prices rise or fall at the time of delivery. For both buyer and seller, this is a way to avoid the risks and uncertainty around price volatility.

When a giant like Hershey uses the futures market to avoid premiums that seek to improve farmers livelihoods, if market prices rise above agreed delivery prices, this only benefits the futures brokers, not farmers.

The only guaranteed stability for African farmers is for chocolate makers to buy directly from farmer cooperatives (or their representatives) at government-instituted farmgate prices plus the living income differential.

According to Al Jazeera English , some farmers in Ivory Coast acknowledged receiving the LID from Tony’s Chocolonely, Mondelez, and Ferrero while other farmers had no clue such a premium exists.

This report by the Qatari news outlet conflicts with an earlier report by Reuters about Mondelez and Hershey refusing or avoiding paying the LID. There’ve been class suits against chocolate giants like Mondelez, Mars, Hershey and Nestle for encouraging slave labour on West Africa cocoa farms. Some brands owned by these major players include M &M’s, Milky Way, Galaxy, Maltesers, SNICKERS, etc., (for Mars), Hershey’s Kisses, Hershey’s Exotic Dark, Reese’s, 5TH Avenue, etc., (for Hershey) and KitKat, Quality Street, Smarties, Matchmakers, etc., (for Nestle).

A 2024 suit accused Mondelez of paying pittances to farmers, pushing farmers to use child and slave labour. Mondelez owns Cadbury, the UK’s bestselling chocolate brand.

The truth is that consumers may not know how transparent companies are with their relationships with cocoa producers. This only makes the fight to improve the income of the African cocoa farmer difficult.

Higher Market Prices do not Necessarily Translate into Better Incomes for Cocoa Farmers

Higher prices do not automatically offset costs of production unless the prices are set to improve producer incomes. Current high prices, including futures prices, are a result of bean shortage from poorer yields, not a consequence of wealth redistribution. Farmers who spent more to mitigate the impact of climate change-induced disease will not necessarily see bigger profits.

If farmers’ produce had already been sold in futures exchanges, higher spot prices driven by poor harvests do not mean that farmers gain. On the contrary, they lose more as the contract quantity must still be supplied.

Because of regulation and government intervention to protect African farmers from poor prices and volatile market conditions, a downside to current price spikes is that African farmers in Ivory Coast and Ghana only benefit 40-50% of global prices. Meanwhile in South America, cocoa producers benefit as much as 90% of global prices.

This disparity in the incomes of cocoa farmers in West Africa and South America lie in how the markets operate. Africa was set up as raw materials market by colonisers, leading to the current dependency on cocoa and other commodities. This has left West African producers vulnerable to market volatility, necessitating governments to step in with price controls. The main cacao markets, Ghana and Ivory Coast, are controlled (which isn’t the case for Cameroon). These largest producer countries seek control over how much they are paid for their beans to end decades of colonial rule.

That’s not the case in South America with liberalised markets, where producers also have better access to capital. While some African producers are shutting down due to current crises, producers in South America are jumping on the opportunity to benefit from the rising prices.

As the West ultimately controls supply and demand, they manipulate prices and shift narratives as they see fit. If wealth is redistributed such that African governments are not forced to control prices in agricultural markets, chocolate would become more ethical. Which is why we do not believe that lab-grown chocolate is the solution to the ills of the chocolate industry. More on that below.

What are Fair Prices for African Cocoa Farmers?

It’s sad but true: fair trade is not always fair to the African cocoa farmer. First the fair trade price is not enough to cover living expenses, being only about 5 to 15% more than farmgate prices. Second, to get certified, already poor farmers must spend, sometimes as much as a years’ worth of yield for audit fees. Third, fairtrade premiums do not go directly to the farmer like the Living Income Differential does. Instead, the extra money divides itself along the way to cover salaries and operations cost in fairtrade farmer cooperatives. The little increment offered by fairtrade is not worth the hassle to get certification.

LEARN MORE: What REALLY is Ethical Chocolate? Going Beyond Certifications

Ivory Coast’s cocoa board believes that cocoa must be bought at a minimum of $2600 per tonne for farmers to make a decent income. If you add the Living Income Differential to that minimum, the price should stand at a minimum of $3000 per tonne or at least $3 per kg. This is a minimum price, still not enough, but as a wealth redistribution price intentionally paid to benefit farmers, it is better than high prices fuelled by poor yields and bean shortage.

A fair price for African cocoa farmers is a price that would match the Anker living wage for each region. That is several times higher than fair trade. At Bantu Chocolate, we pay our farm workers 6X higher than the commodity price and 3X higher than the fair trade price.

Lab-Grown Chocolate, Another Industry Initiative to Deprive the Cocoa Farmer of their Meagre Income Altogether

Higher cocoa prices are not necessarily due to poor cacao yields. Higher cocoa prices are also influenced by narratives from the West that claim that cacao is disappearing. This narrative ultimately encourages consumers towards lab-grown chocolate and fake chocolate.

Even if creators of lab-grown chocolate claim their primary concern is eco-sustainability, lab-grown chocolate still falls short of being ethical. As the head of impact at Tony’s Chocolonely already confessed, manufacturers of natural chocolate can choose between improving farmer incomes or keep maximising profits at the expense of poverty. So, an ethical solution to the cocoa-chocolate crisis is not sidestepping impoverished farmers to create chocolate in the laboratory.

In West Africa alone, there are about 2 million cocoa farmers, many who depend on cocoa as their primary source of income. Taking that away from them, instead of solving the fundamental cause of farmer poverty is unethical. Wealth redistribution down the supply chain can help farmers diversify their income sources as well as maintain their cocoa farms with better inputs. Everybody in the supply chain benefits.

What High Cocoa Prices Mean for Consumers

The underlying causes of current high cocoa prices cannot be fixed overnight. Cocoa prices are expected to keep rising, and even though chocolate companies are reluctant to pass the high costs to the consumer, they can’t be hesitant forever as businesses do not generally accept lower profits. Analysts are predicting high chocolate prices at the end of this year or early next year. There’s also the possibility that chocolate makers would shrink their pack sizes or simply reduce the amount of cocoa in their recipes. Dark chocolate may suffer more from these possible responses to higher prices.

References

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-cocoa-hershey-delivery-idUSKBN2802X5/

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41287-023-00612-x

https://www.foodbev.com/news/ivory-coast-raises-cocoa-farmgate-price-by-50/

Chocolate Extinction: Fact vs. Fiction + What Chocolate Lovers Can Do

Chocolate ExtinctionFact vs. Fiction, What Consumers Can Do Share On Facebook Twitter Email Is the world really running out of chocolate? Not really. Currently the global […]

Corporate Chocolate Gifting Ideas to Appreciate Employees and Delight Clients

Corporate Chocolate GiftingHow to Appreciate Employees & Delight Clients Share On Facebook Twitter Email When it comes to corporate gifting, a one-gift-fits-all approach just doesn't cut […]

Cacao Supper Club at Home: Guide to Tasting Chocolate, Cacao Tea, and Pulp Juice

Cacao Supper Club at HomeGuide to Tasting Chocolate, Cacao Tea, and Pulp Juice Share On Facebook Twitter Email Imagine gathering around the table with a few […]