Welcome to Bantu Chocolate

March 11, 2022

Sri Lanka and India

The introduction of cacao into these territories may have likely come through the East Indies. The Criollo species was also brought to India in 1798 from Moluccas in Indonesia.

Brazil

Although there’d always been wild cacao trees in the Amazon basin, Brazil and Ecuador were the first countries to cultivate the forastero species in the 18th century. In the Brazilian state of Bahia, cacao was planted allegedly by a French who brought seeds from the state of Para, still in Brazil, in 1746. It was not until 1825, though, that Brazil exported any cacao.

Ecuador

It is not known whether there was cacao cultivation in Ecuador before the 17th century. The species planted was the nacional type (unique to Ecuador), probably from wild trees selected for seed from previous plantings. In the 19th century, Ecuador became the largest producer of cacao in the world.

São Tomé

After the independence of Brazil, the amelonado species was taken from Bahia state to São Tomé in 1822. Three decades later, in 1955, it was taken to Fernando Po.

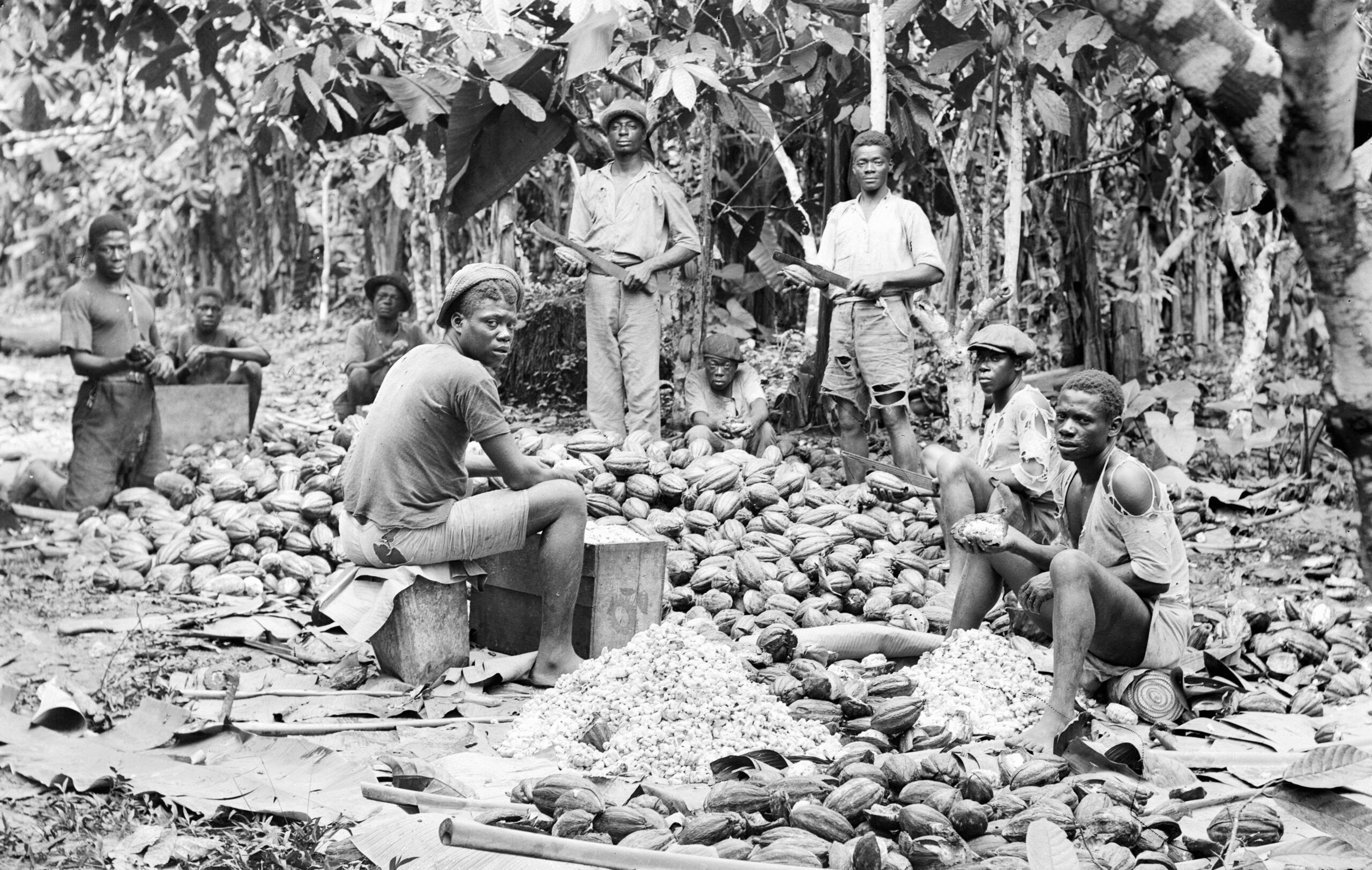

West Africa (Ghana and Nigeria)

From Fernando Po, cacao entered West Africa through Ghana first and then Nigeria to form the basis of its cultivation in Africa. Today, four West Africa countries—Ghana, Ivory Coast, Nigeria, and Cameroon—account for over 70% of the world’s cacao production.

How Did Cacao Get to Africa?

Cacao came to Africa from Brazil in 1822 to the island of São Tomé. From São Tomé, cacao was taken to the island Fernando Po (Bioko in Equatorial Guinea) in 1955. In 1870, Ghanaian farmer Tetteh Quarshie travelled to Fernando Po and returned in 1876 with cacao seeds which he planted with success. From Ghana, cacao made its way to other African countries.

Read detailed history of cacao in Africa.

Is Cacao Native to Africa or South America?

The written history of cacao began in Mesoamerica, possibly as early as the mid-third century A.D. But this doesn’t give a full picture of the origin of cacao. What is generally accepted is that the chocolate tree is native to the Americas. West Africa, however, is the largest producer of cocoa beans worldwide.

Sources:

Cocao by G.A.R Wood and R. A Lass, Fourth Edition

Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A Cultural History of Cacao, Edited by Cameron L. McNeil

Naked Chocolate: The Astonishing Truth About the World’s Greatest Food, by David Wolfe and Shazzi