Welcome to Bantu Chocolate

March 11, 2022

Difference Between Cacao and Cocoa Plus Health Benefits

May 6, 2022Cocoa in West Africa

Cash Crop Dependency, Social Impact & Influence of Colonialism

West Africa produces over 70% of the world’s cocoa beans, with the leading countries being Ivory Coast, Ghana, Nigeria, and Cameroon. This record surpasses that of North and South America, where the chocolate tree originated.

This article looks at the origins, social impact, and challenges of cultivating cocoa in West Africa.

History of Cocoa in Africa

It is uncertain when cacao was introduced to Africa, but it is widely known that the Portuguese brought the cacao tree from South America (most likely from Brazil) to the African tropics. As early as 1822, the Portuguese planted cacao on the island of San Thomé (São Tomé) and serious cultivation only picked up five decades later in 1870. By 1895, this island was exporting a million kilograms of cacao beans. From Sao Tome, cacao seeds were taken to Fernando Po, an island in modern-day Equatorial Guinea.

In 1970, Tetteh Quarshie, a farmer from the Gold Coast (today Ghana) travelled to Fernando Po and brought cacao seeds to Ghana. His success with planting cacao in his village inspired friends and relatives to adopt cacao farming. Seeing the success, missionaries also imported cacao seeds into the country. From Ghana, cacao made its way to Nigeria and Sierra Leone.

Regarding Nigeria, it is alleged that in 1874 a native chief, Squiss Banego, also brought cacao from Fernando Po and established a cacao plantation in Bonny Island, at the very heart of the Niger Delta region of Nigeria, only a couple of kilometers away from Cameroon. His plantation flourished and helped to spread cacao cultivation in Nigeria.

Around 1892, the Germans introduced cacao in Cameroon from South America and the West Indies. What is significant here is that the Germans introduced the trinitario specie in Cameroon unlike the amelonado in Ghana and Nigeria.

Social Impact of Cocoa in West Africa: Cash Crop Dependency

There are over 2 million farmers of cocoa in West Africa, producing over 70% of the world’s cocoa beans. But only about 3% of the world’s chocolate is manufactured in Africa. This means that Theobroma cacao is grown in Africa mainly as a cash crop and exported as a primary commodity to chocolate-producing Europe and America.

On the surface, this would seem like cacao cultivation brings in a lot of money to African economies and cocoa farmers through foreign exchange. While there are a few millionaires from cocoa farming, many farmers make less than $1 per day from cocoa in West Africa and depend on the cash crop to feed their families, send their children to school, and pay medical bills.

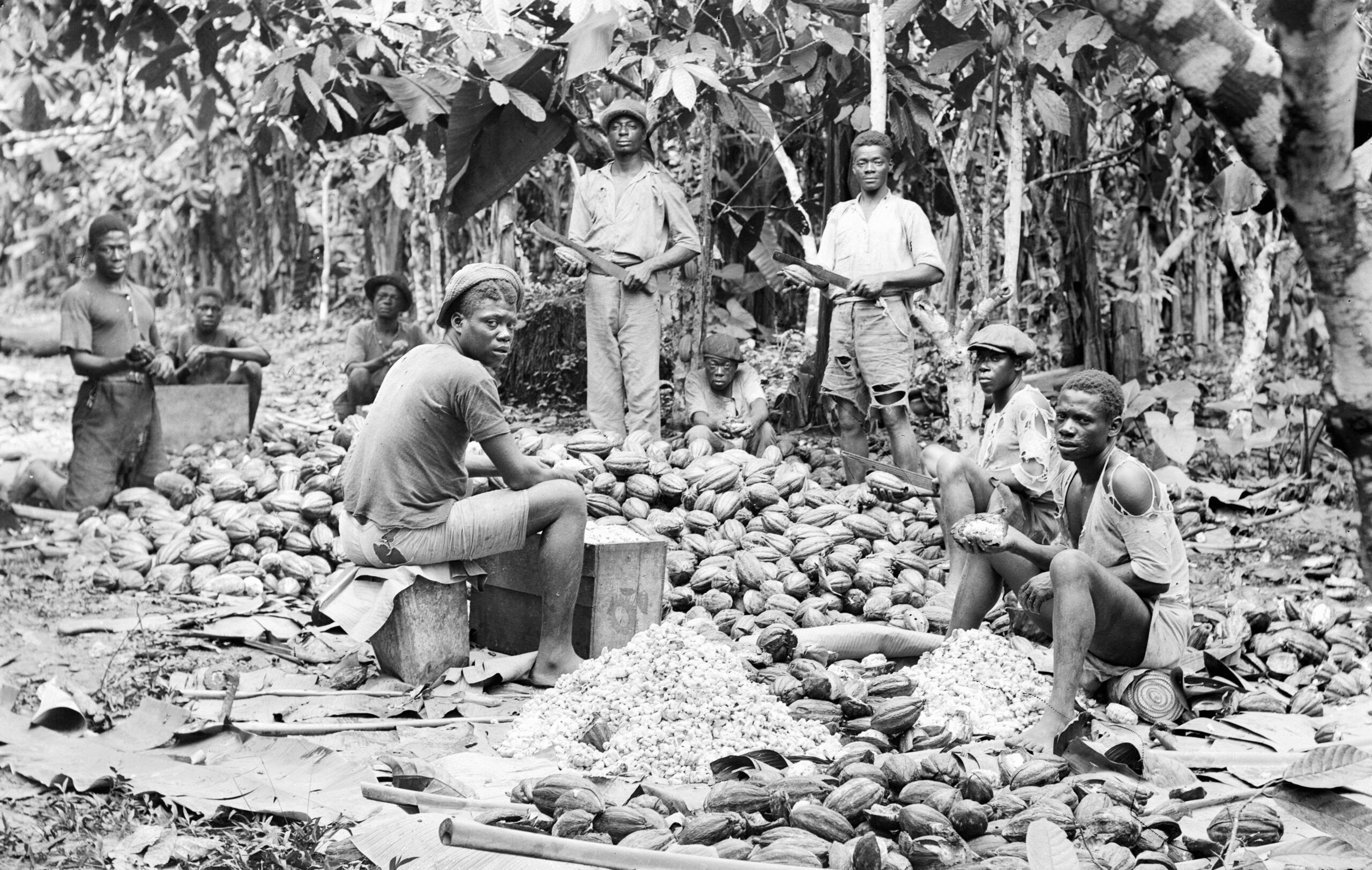

Often, there’s child labor or forced labor to reduce the cost of production to maximize profits. There’s also deforestation as farmers cut down new forests to expand their farmland.

Before the Europeans colonized Africa, Africans farmed mostly food crops to feed their households. Colonization imposed the cultivation of cash crops for export to generate revenue that supported the colonial governments.

At independence, post-colonial governments continued with agricultural policies and structures that favored cash crop production to the detriment of food production. This led to the dependency of African economies and societies on agricultural export to gain access into international marketplaces.

This dependency remains, despite fluctuating global market prices. Cacao cultivation continues to expand in West Africa as many farmers dream of a brighter future.

The Impact of Colonialism on the Cultivation of Cocoa in West Africa

Europe designed its African colonies as suppliers of primary commodities to the capitalist West. This has left a legacy that is both good and bad, especially for a crop like cacao which is not native to Africa, but only cultivated for export.

The Good

Colonial masters encouraged cacao production, sometimes owning some of the main plantations and pioneering research on plant diseases. This introduction and encouragement of cash crop production earned huge sums of money to the local farmer during profitable seasons when cacao was gold.

The revenue from the export trade supported the colonial government’s administration and creation of infrastructures like roads and hospitals.

Africa’s leading position today in cacao bean production is largely an impact of colonial policies that created an entry of African produce into the international market. Local farmers, even when profits are not sustainable, can still send their children to school or pay medical bills.

The Bad

Africa’s involvement in the West’s capitalism left the colonies vulnerable to the whims of the world market over which it had no control. The colonial governments set market prices, which sometimes forced the local farmers to sell their produce to middlemen and authorized buying firms at very low prices. Even when a price increase was justifiable, farmers were still deprived of maximum profits through low prices set to control inflation and limit the African purchasing power.

Colonialism laid the foundation for the dependency of African economies on agricultural exports in the form of raw materials instead of industrialization. Today, that foundation stands as a solid structure where Africa exports cacao as a primary commodity and imports chocolate as a final product.

Much of the profits in the supply chain go to middlemen and Big Chocolate while the first link in the chain, the local African farmer, battles with poverty because of unstable prices of cacao at the world market.

The leading cacao-producing countries now have marketing boards, but they are ineffective at shielding their economies and farmers from price fluctuations due to economic and political upheavals that affect demand in consumer countries.

Besides price-setting, sometimes colonial governments instituted holdups of produce and banned exports to certain markets. for example, Britain banned exports to the USA during World War II, to protect their own interest. Also, during WW II cacao was relegated to a non-priority commodity, and the British colonial government only bought the crop to squash any riot from the African communities.

Today, Africa still depends on the West for its market and investments, with farmers left at the mercy of a global market they don’t control.

Challenges Faced by Cocoa Farmers in West Africa

Besides battling with volatile global market prices as the largest bean producers, African cacao farmers face challenges like farmers elsewhere.

Insect attack: sap-sucking bugs known as capsids feed on plant stem and pods, damaging the plant with their toxic spit. The wounds they inflict on the plant give room for opportunistic attacks by fungi. According to reports from different parts of West Africa, insect attacks can cause damage between 30-75% of cacao losses. The cure is to provide a uniform shade over the cacao trees to limit sunlight and therefore break the life cycle of capsids. Insecticides are also used.

Diseases: mostly black pod disease (fungal) and cocoa swollen shoot virus. Using pesticides and removal of infected shoots and plants are ways farmers handle these parasitic invasions.

Deforestation: When farms get old, more natural forests are cut down for new farmland. This leads to emission of greenhouse gases, leaching, soil erosion, and destruction of biodiversity. The remedy is agroforestry, where cacao cultivation is done alongside other trees and shrubs.

Climate change: Increases in temperature causes trees to become water-stressed, decreasing yields.

Why Are Cocoa Farmers in West Africa so Poor?

There are various reasons for many poor cacao farmers in West Africa.

1. The largest producers of cacao beans don’t control the market prices, which are usually not profitable, coupled with high taxes on exports.

2. Many farmers are owners of small plots or sharecroppers. That means small yields or yields shared with landlords.

3. In Ghana and Ivory Coast, middlemen cut their share of the global market price, giving just about 60-70% to farmers who bear the brunt of production cost.

4. Chocolate is a luxury item in much of Africa, and Africa manufactures just about 3% of the world’s chocolate. So farmers depend on exports to make profits for their sweat and are forced to sell even when prices fall.

5. Even though some African governments have placed premium prices per ton of cacao over future standard global market prices as from 2020, chocolate manufacturers in the West are reluctant to spend more on raw materials. If these governments were to impose trade bans to force price increase, it is likely that poor farmers desperate for money would smuggle their harvest.

Current Initiatives to Ensure Sustainable Cocoa in West Africa

As more people question the sources of their food and how the foods are processed, chocolate companies and NGOs are keen on eliminating practices that mar the image of the supply chain.

Some chocolatiers have welcomed the imposed premium prices. There is the Cocoa and Forests Initiative, an initiative by 35 major cocoa and chocolate companies and the governments of Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire to end deforestation and forests degradation. Partnerships between producing countries, consumer nations, cocoa and chocolate companies, and civil societies seek to end child labor and poverty. Other initiatives aim at distributing disease-resistant varieties of Theobroma cacao.

The governments of Ivory Coast and Ghana have strategies for climate-smart cocoa production systems to anticipate severe damages to plant health by climate change. These cacao-giants also desire an OPEC-like organization for cacao, which should position cacao producers to determine global market prices.

Cocoa in West Africa – What’s the Future?

The cacao trade is an important part of the West African economy. Though saddled by an inherited colonial-style export-driven system, volatile global market prices, diseases, and low local consumption of finished products, the cash crop cultivation is not going away soon as many farmers still see a profitable future in the cocoa sector. This, however, is only possible with initiatives that ensure sustainability.

References

Darkoh, Michael B. K., and Mohamed Ould-Mey. “CASH CROPS VERSUS FOOD CROPS IN AFRICA: A CONFLICT BETWEEN DEPENDENCY AND AUTONOMY.” Transafrican Journal of History 21 (1992): 36–50. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24520419.

Olorunfemi, A. “Effects of War-Time Trade Controls on Nigerian Cocoa Traders and Producers, 1939-45: A Case-Study of the Hazards of a Dependent Economy.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 13, no. 4 (1980): 672–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/218201.

CHOCOLATE CRISIS Climate Change and Other Threats to the Future of Cacao by DALE WALTERS, UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA PRESS Gainesville

‘WHEN EUROPE SNEEZES…?’ A Comparative Analysis of the African Experience of the Great Depression and the Second World War By Ushehwedu Kufakurinani and Honest Koke

Chocolate Extinction: Fact vs. Fiction + What Chocolate Lovers Can Do

Chocolate ExtinctionFact vs. Fiction, What Consumers Can Do Share On Facebook Twitter Email Is the world really running out of chocolate? Not really. Currently the global […]

Corporate Chocolate Gifting Ideas to Appreciate Employees and Delight Clients

Corporate Chocolate GiftingHow to Appreciate Employees & Delight Clients Share On Facebook Twitter Email When it comes to corporate gifting, a one-gift-fits-all approach just doesn't cut […]

Cacao Supper Club at Home: Guide to Tasting Chocolate, Cacao Tea, and Pulp Juice

Cacao Supper Club at HomeGuide to Tasting Chocolate, Cacao Tea, and Pulp Juice Share On Facebook Twitter Email Imagine gathering around the table with a few […]